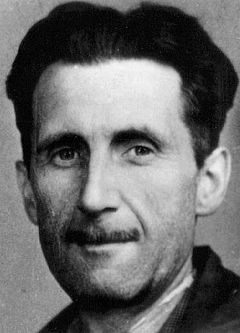

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known as George Orwell, perhaps considered as the twentieth century’s best chronicler of English culture. Orwell wrote fiction, polemical journalism, literary criticism and poetry. He was best known for the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and the satirical novella Animal Farm. Together the two books have sold more copies than any two books by any other twentieth-century author. His Homage to Catalonia, an account of his experiences as a volunteer on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War, together with his numerous essays on politics, literature, language and culture, are widely acclaimed.

Wile fighting as a volunteer on the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War, George Orwell was staying at the Hotel Continental in Barcelona. He later got wounded and wrote the famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, wile recovering in the Hotel (The novel was published in 1949). Today you can find the Plaça George Orwell in Barrio Gothic, Barcelona and there is a street named after him in Mallorca.

George Orwell was an English author and journalist who’s work is marked by keen intelligence and wit, a profound awareness of social injustice, an intense, revolutionary opposition to totalitarianism, a passion for clarity in language and a belief in democratic socialism.

Homage to Catalonia is George Orwell’s personal account of his experiences and observations in the Spanish Civil War. The first edition in Europe was published in 1938, but the book was not published in the United States until February 1952.

Homage to Catalonia is George Orwell’s personal account of his experiences and observations in the Spanish Civil War. The first edition in Europe was published in 1938, but the book was not published in the United States until February 1952.

Chapter nine

…They had taken my rifle away again, and there seemed to be nothing that one could usefully do. Another Englishman and myself decided to go back to the Hotel Continental. There was a lot of firing in the distance, but seemingly none in the Ramblas. On the way up we looked in at the food-market. A very few stalls had opened; they were besieged by a crowd of people from the working-class quarters south of the Ramblas. Just as we got there, there was a heavy crash of rifle-fire outside, some panes of glass in the roof were shivered, and the crowd went flying for the back exits. A few stalls remained open, however; we managed to get a cup of coffee each and buy a wedge of goat’s-milk cheese which I tucked in beside my bombs. A few days later I was very glad of that cheese.

At the street-corner where I had seen the Anarchists begin firing the day before a barricade was now standing. The man behind it (I was on the other side of the street) shouted to me to be careful. The Civil Guards in the church tower were firing indiscriminately at everyone who passed. I paused and then crossed the opening at a run; sure enough, a bullet cracked past me, uncomfortably close. When I neared the P.O.U.M. Executive Building, still on the other side of the road, there were fresh shouts of warning from some Shock Troopers standing in the doorway—shouts which, at the moment, I did not understand. There were trees and a newspaper kiosk between myself and the building (streets of this type in Spain have a broad walk running down the middle), and I could not see what they were pointing at. I went up to the Continental, made sure that all was well, washed my face, and then went back to the P.O.U.M. Executive Building (it was about a hundred yards down the street) to ask for orders. By this time the roar of rifle and machine-gun fire from various directions was almost comparable to the din of a battle. I had just found Kopp and was asking him what we were supposed to do when there was a series of appalling crashes down below. The din was so loud that I made sure someone must be firing at us with a field-gun. Actually it was only hand-grenades, which make double their usual noise when they burst among stone buildings…